The Contribution of JUDO to Education

One form is what I named "representative form." This is a way of representing ideas, emotions, and different motions of natural object by the movements of limbs, body and neck. Dancing is one instance of such, but originally dancing was not devised with physical education for its object and can therefore not be said to fulfil those requirements. But it is possible to devise special kinds of dancing made to suit persons of different sex and mental and physical condition and made to express moral ideas and feelings, so that conjointly with the cultivation of the spiritual side of a nation it can also develop the body in a way suited to all.

This "representative from" is, I believe, in one way or other practised in America and Europe, and you can, I think, imagine what I mean:therefore I shall not deal with it any further here.

There is one other form which I named "attack and defence form." In this, I have combined different methods of attack and defence, in such a way that the result will conduce to the harmonious development of the whole body. Ordinary methods of attack and defence taught in Jujitsu cannot be said to be ideal for the development of the body, therefore, I have especially combined them so that they fulfil the conditions necessary for the harmonious development of the body. This can be said to meet two purposes: (1) bodily development, and (2) training in the art of contest, As every nation is required to provide for national defence, so every individual must know how to defend himself. In this age of enlightenment, nobody would care to prepare either for national aggressions or for doing individual violence to others. But defence in the cause of justice and humanity must never be neglected by a nation or by an individual.

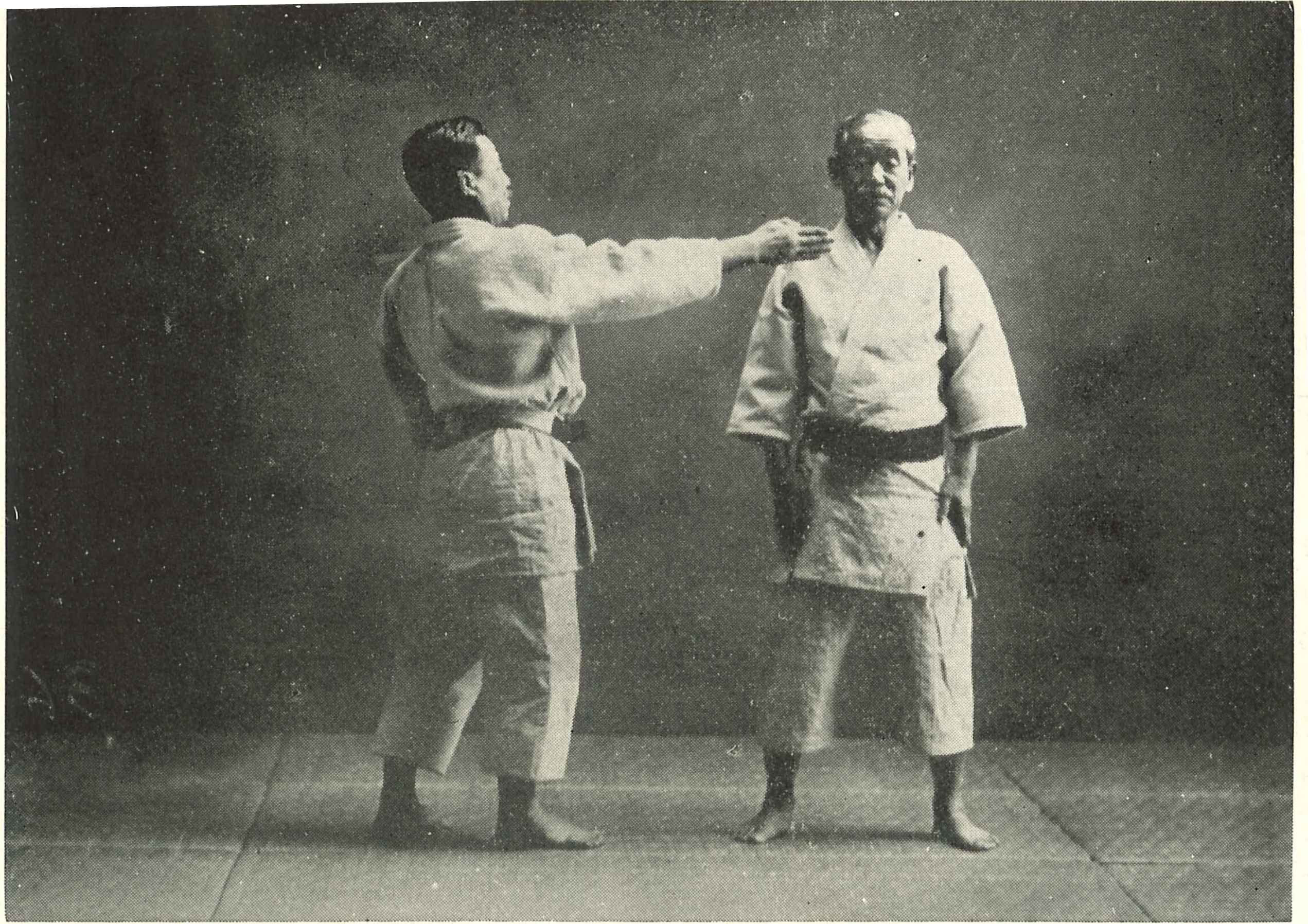

This method of physical education in attack and defence form, I shall show you by actual practice. This is divided into two kinds of exercises: one is individual exercise and the other is exercise with an opponent (as demonstrated).

From what I have explained and shown by practice, you have no doubt understood what I mean by physical education based on the principle of maximum-efficiency. Although I strongly advocate that the physical education of a whole nation should be conducted on that principle, at the same time I do not mean to lay little emphasis on athletics and various kinds of martial exercise. Although they cannot be deemed appopriate as a physical education of a whole nation, yet as a culture of a group or groups of persons, they have their special value and I by no means wish to discourage them, especially Randori in Judo.

One great value of Randori lies in the abundance of movements it affords for physical development. Another valus is that every movement has some purpose and is executed with spirit, while in ordinary gymnastic exercises movements lack interest. The object of a systematic physical training in Judo is not only to develop the body but to enable a man or a woman, to have a perfect control over mind and body and to make him or her ready to meet any emergency whether that be a pure accident or an attack by others.

Although exercise in Judo is generally conducted between two persons, both in Kata and in Randorl, and in a room specially prepared for the purpose, yet that is not always necessary. It can be practised by a group or by a single person, on the playground or in an ordinary room. People imagine that falling in Randori is attended with pain and sometimes with danger. But a brief explanation of the way one is taught to fall will enable them to understand that there is no such pain or danger.

I shall now proceed to speak of the intellectual phase of Judo. Mental training in Judo can be done by Kata as well as by Randori, but more successfully by the latter. As Randori is a competition between two persons, using all the resources at their command and obeying the prescribed rules of Judo, both parties must always be wide awake, and be endeavouring to find out weak points of the opponent, being ready to attack whenever opportunity allows. Such an attitude of mind in devising means of attack tends to make the pupil earnest, sincere, thoughtful, cautious and deliberate in all his dealings. At the same time one is trained for quick decision and prompt action, because in Randori unless one decides quickly and acts promptly he will always lose his opportunity either in attacking or in defending.

Again, in Randori each contestant cannot tell what his opponent is going to do, so each must always be prepared to meet any sudden attack by the other. Habituated to this kind of mental attitude, he develops a high degree of mental composure?of "poise." Exercise of the power of attention and observation in the gymnasium or place of training, naturally develops such power, which is so useful in daily life.

For devising means of defeating an opponent, the exercise of the power of imagination, of reasoning and of judgment, is indispensable, and such power is naturally developed in Randori. Again, as the study of Randori is the study of the relation, mental and physical, existing between two competing parties, hundreds of valuable lessons may be derived from this study, but I will content myself for the present by giving a few more examples. In Randori we teach the pupil always to act on the fundamental principle of Judo, no matter how physically inferior his opponent may seem to him and even if he can by sheer strength easily overcome the other. If he acts against this principle the opponent will never be convinced of his defeat, whatever brutal strength may have been used on him. It is hardly necessary to call your attention to the fact that the way to convince your opponent in an argument is not to push this or that advantage over him be it from power, from knowledge, or from wealth, but to persuade him in accordance with the inviolable rules of logic. This lesson that suasion, not coercion, is efficacious―which is so valuable in actual life―we may learn from Randori.

Again we teach the learner, when he has recourse to any trick in overcoming his opponent, to employ only as much of his force as is absolutely required for the purpose in question, cautioning him against either an over- or an under-exertion of force. There are not a few cases in which people fail in what they undertake simply because they go too far, not knowing where to stop, and vice versa.

To take still another instance, in Randori, we teach the learner, when he faces an opponent who is madly excited, to score a victory over him, not by directly resisting him with might and main, but by playing him till the very fury and power of the latter expends itself.

The usefulness of this attitude in everyday transactions with others is patent. As is well known, no amount of reasoning could avail us when we are confronted by a person who is so agitated as to seem to have lost his temper. All that we have to do in such a case is to wait until his passion wears itself out. All these teachings we learn from the practice of Randori. Their application to the conduct of daily affairs is a very interesting subject of study and is valuable as an intellectual training for young minds.

I will finish my talk about the intellectual phase of Judo by referring shortly to the rational means of increasing knowledge and intellectual power.

If we closely observe society, we notice everywhere the way in which we foolishly expend our energy in the acquisition of knowledge. All our surroundings are always giving us opportunities of gaining useful knowledge, but are we not constantly neglecting the best use of such opportunities? Are we always making the best choice of books, magazines and newspapers we read? Do we not often find out that the energy which might have been spent for acquiring useful knowledge is often used for amassing knowledge which is prejudicial not only to self but also to society?